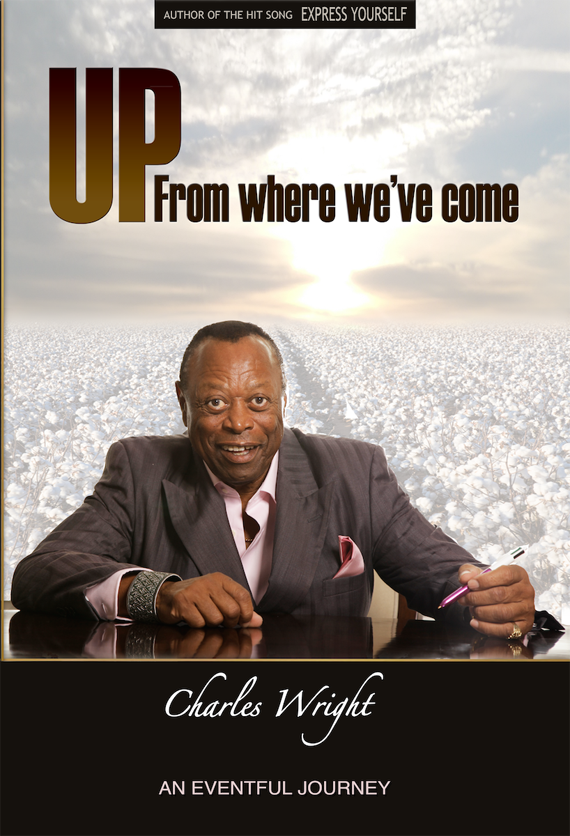

In our first book review we look at the forthcoming autobiography from soul funk legend Charles Wright who recounts his childhood years living in Clarksdale Mississippi during the era of segregation.

In 1970 the soul/funk standard ‘Express Yourself’ was released on Warner Brothers Records, reaching #3 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles. The song has gone down in music history as one of the most played soul records of all time, as well as being covered and sampled countless times by acts from N.W.A to Labrinth. As with these classic songs, often the original creators go without due credit, and this is definitely the case with Charles Wright. Wright, along with the 103rd Street Rhythm Band crafted this timeless hit, but most outside of the soul community probably won’t know his name. But now Wright is seeking to change that with his new autobiography, Up From Where We’ve Come.

However, if you’re looking to learn more about how Wright fell into music and developed songs such as ‘Express Yourself’ you might be a bit disappointed to find that this book does not cover this at all. In the prelude to the book, Wright states that this book will, hopefully, be the first in a series of books telling his life story. This first one recounts Wright’s childhood growing up in Clarksdale, Mississippi in an era when Jim Crow reigned supreme.

It’s worth at this point detailing some of background to Wright’s book. Born in 1940 in the Deep South, Wright grew up in an America segregated by race. Although the Union had won the Civil War the century previously, a war fought over the slave system that had made Southern white landowners rich, and the slaves were supposedly given their freedom after emancipation, for many very little had changed by the time Wright was born. Slavery was replaced by another form of servitude, namely sharecropping. Now, instead of slaves being owned by the landowners, the landowners would provide some of their land to the newly ‘freed’ blacks, as well as poor white farmers, along with some rudimentary housing, equipment and maybe even a mule; a local merchant would provide the farmer with credit to purchase food and supplies. In return, at harvest the sharecropper would take a share of the crop produced; the sharecropper would take the rest, minus anything else was owed.

This was the arrangement that Wright was born into. Both his parents and his older siblings would work the cotton fields, picking upwards of one hundred pounds of cotton a day depending on the harvest. Despite growing up in what we could call today abject poverty, Wright makes no claim to have an unhappy childhood; in part this is probably down to the efforts his parents made, particular his mother, in providing him and his siblings with whatever they could to make their lives marginally better.

Wright spent the first ten years of his life in Clarksdale on various farms and in various shacks provided to the family by the landowners. The Wright family spent most of the decade on land owned by a Mr Miles, a God-fearing man who didn’t share his Christian brotherly love with Wright’s father. Similarly, the local merchant, a Mr Brookings, was abusive and racist towards the Wright family; yet economics would always trump racism, for Mr Brookings needed trade with the large Wright family to make any money for himself.

One of the stories that stand out in the book is the first time that Wright took a ride in a car into Clarksdale with the rest of his family. His amazement at being in a car for the first time is fascinating to read for a modern audience who’ve been around cars all their lives. Yet their ownership of the car did not last long: Wright’s father had bought the car with the financial help of Mr Miles, but further financial woes and the devious assistant to Mr Brookings, a man named Leo, conned Wright into selling the car, a blow to Wright’s father who tried for years to better his family’s desperate situation.

Another story that stands out is that of Wright’s brother McClain. At a local gathering, McClain shot a boy by the name of Bill Williams to death after a petty argument between the two; Wright claims that McClain did not know that the gun was loaded, and accidentally killed Williams. To avoid the law, as well as Williams’ fierce brothers, McClain fled only to remerge three years later as a preacher. One of the best quotes from the book deals with McClain’s new career; being a good-looking, young preacher ‘all the ladies in Clarksdale immediately took to and gave him access to his choice among them’.

The strength of the book however is providing the reader with a first hand account at what it was like growing up on a sharecropping farm, and what is was like to grow up in segregated Mississippi. One of the striking things Wright tells us about is that even the cemeteries of the South were segregated. Wright attempts no effort to explain how sharecropping and segregation came into being, but that isn’t what he’s trying to achieve here. Furthermore, the book is written in how Wright actually speaks, rather than standardised English, which makes it at times a little difficult to follow. That said, this tale would work excellently as an audio-book narrative by Wright himself. But then Wright is trying to provide an honest, personal account of his life and what he, along with thousands of other African-Americans in the South endured. Despite the sometimes clunky narrative, Wright achieves this.

Two things really stand out in the book for us. The first of these is the awfulness of the American system towards African-Americans at this time. Far from allowing blacks to pursuit life, liberty and happiness, the system of segregation ensued the complete opposite, keeping African-Americans locked into a pattern of servitude and poverty right up until the forties and fifties; it was only in the sixties that minorities in America were allowed to exercise their full rights as guaranteed by the Constitution. Wright details the system that Mr Miles and other sharecroppers used to keep these Americans working the land, a system known as the ‘The Triple B’ system: ‘A nigger is at his Best when Bent until Broken’. This system forced the African-Americans working on the white landowners property to borrow money during the tough months of winter, to pay back with interest the following harvest if the crop yield allowed. If not, that money would be borrowed on the next year’s crop, keeping the cycle of debt going. Wright claims ‘that during our entire careers, merely came close to breaking even, but only twice.’

Wright’s father had to accept the poor terms offered by Mr Miles; sharecropping may have been terrible, but for many poor African-American Southerners it was there only chance. The system was rigged against the Wrights, and they knew it. But they had to comply with it, which angered the young Charles, who writes that his parents appeared to make it their ‘moral obligation to comply with his [Mr Miles’] twisted outlook’. Wright was acutely aware of the teachings of Christianity, noting that both Mr Miles and his father were religious men, asking ‘why would such a religious man as my father, who claimed to know all about right and wrong, be so willing to validate his wicked behaviour?’

The second thing that we have taken away from Wright’s autobiography is his initial eagerness to join the family in picking cotton in the Mississippi fields. Wright writes of his excitement of being allowed into the fields with his parents and siblings to pick the cash-crop. Yet the excitement was short-lived: picking cotton is no easy task, and Wright failed, disappointing his father who had hoped that Wright would unload some of the burden from him. Early after this Wright realised that becoming a field hand under these circumstances was nothing more than to ‘rob you of identity and sap the life out of once vital individuals. Reading this book, one is struck by the way that growing up Wright was conditioned into the lifestyle of a poor black sharecropper as if it was simply normal. It’s hard to imagine that today, but back then it probably was normal, and incredibly sad to think that, for a young black boy it probably was normal. Given the hopelessness of Wright’s situation it is remarkable that he achieved anything at all in a system that was designed to prevent black people doing just that: achieving something beyond picking cotton.

His chance in life came with the decision by Wright’s mother to move to California where Wright had an Aunt. Wright’s father was sceptical about the move: even though he had lived a miserable life as a sharecropper, and that he could not get a job because the landowners in the region conspired to make him unemployable once he left the farms, farming and sharecropping was all he had known. Yet, once Wright’s mother made the move with her daughters, his father decided to join them in Southern California. The journey took days via trains, but the journey hinted at a better life when they could sit anywhere on the train, not just in a ‘coloured’ section. As Wright concludes, ‘I personally felt as though I’d been transported to another planet and given a brand new lease of life. And, oh, what a wonderful, wonderful new beginning!’

Charles Wright’s childhood story is one that seems so far removed from today’s reality, but one that thousands of black Americans had to endure well into the last century. Sadly, a form of the racist and segregated America that Wright grew up in still exists today in a variety of forms, whether it be institutionalised racism in America’s police force, the American justice system, or the fact that African-Americans are likely to live shorter and less richer lives than white Americans. The story Wright vividly paints in his book reminds us of the social progress that the United States has undergone in the past five decades or so, but it also serves as a reminder that much more still needs to be done.

Charles Wright’s new autobiography is out next week – for more information click here.