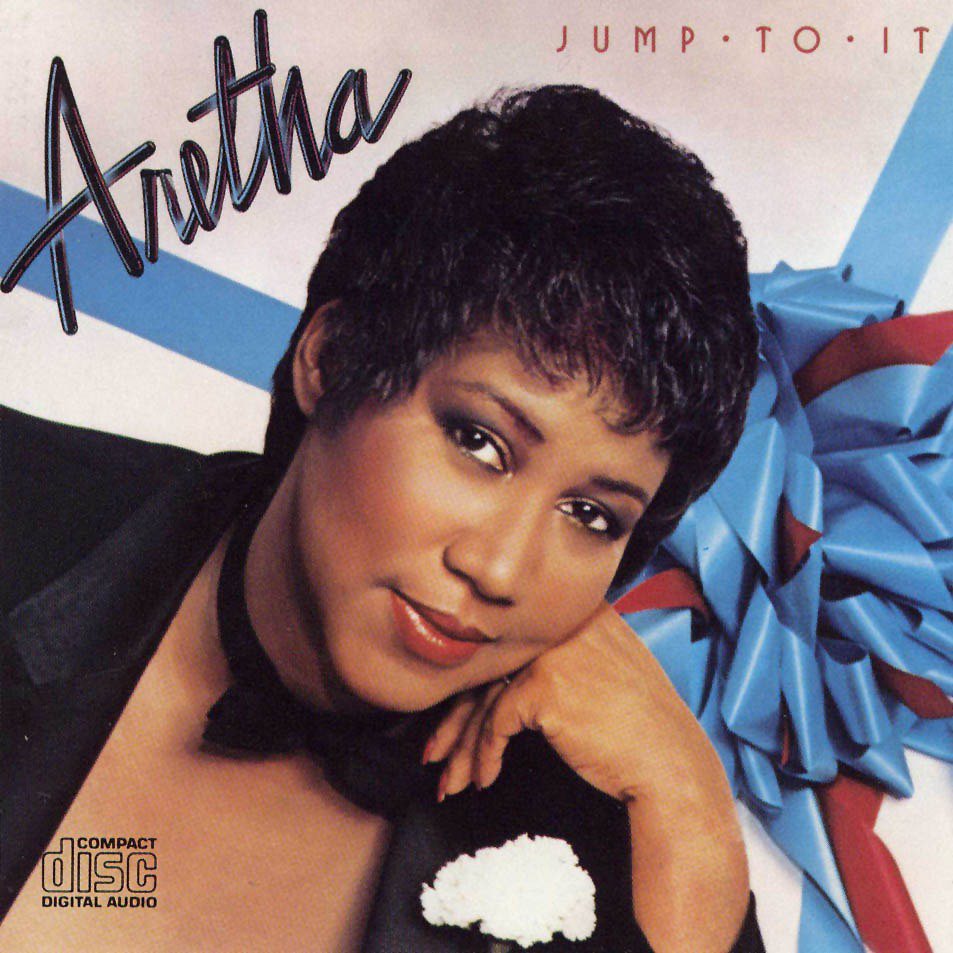

It’s been 35 years since the release of Aretha Franklin’s album Jump To It, written and produced by none other than Luther Vandross. In this Soul Revisited we take a look back at the album, and the Queen of Soul’s legendary diva-ness.

By the early eighties it seemed that the Queen of Soul’s crown was slipping. For critics and fans alike, as well herself, it appeared that Aretha Franklin’s best days were behind her. In 1979 Franklin had left Atlantic Records after three uninspired albums (Sweet Passion, Almighty Fire and La Diva), and went in search of a new label who could reignite her stalling career. A year later she had signed with Clive Davis’s Arista Records, and had released the album Aretha, which featured a cover of the Otis Redding classic ‘Can’t Turn You Loose’. It was a decent effort, and she followed it up with the moderately successful album Love All The Hurt Away, the title track of which featured George Benson. She even won a Grammy for her cover of ‘Hold On, I’m Coming’, but it quickly faded from memory.

Importantly, these Arista-era albums marked a change in Aretha’s sound. Compared with her earlier albums at both Columbia and Atlantic Records, gone were the typically large arrangements, replaced instead by more commercial-orientated arrangements, as well as more eighties sounding instrumentation. What the Queen wanted was commercial hits, not critical praise. She wanted a hit, and she wanted it badly. Frustratingly for Aretha the commercial hits continued to allude her.

In 1982 Davis approached the then-upcoming Luther Vandross to produce Franklin’s next album. Whilst promoting his debut album Never Too Much, Vandross was quoted in Rolling Stone magazine as wanting to produce Franklin. Davis had read the article and made Luther an offer. It was an inspired choice: Vandross, a longtime backing singer for the likes of Chic, Bette Midler and Roberta Flack, was finally finding fame with the release of his debut solo album along with his appearance with the studio group Change on their debut singles ‘The Glow of Love’ and ‘Searching’. Luther had successfully navigated soul in the post-disco area, and initiated the adult contemporary genre in black music with his super-romantic ballads, in particular his version of ‘A House is not a Home‘, arguably his first real masterpiece.

Vandross’s new found fames and infectious soul grooves made him perhaps the perfect choice to revive the career of the Queen of Soul. He was a fan of the great female voices in soul, growing up adoring the vocals of Patti LaBelle (he was rumoured to have started her first ever fan club), Dionne Warwick (he once lied about being related to her at college), and Aretha herself.

Vandross began work on the album with bassist Marcus Miller, an equally talented musician and songwriter who would go on to become one of the most respected musicians in jazz and soul. Yet things didn’t get off to a glowing start. In an interview with David Ritz, who ghost-wrote Aretha’s autobiography, then his own, more revealing biography of the singer, Aretha had called Luther to discuss working together. Luther excitedly grabbed the phone, answering simply “Aretha?” to which the Queen of Soul replied cooly, “Yes, this is Miss Franklin, is this Mr Vandross?”

Eventually, the two got into the studio together, but it wasn’t an easy relationship. Aretha, the Queen of Soul, seemed to resent the approach Luther had in the studio, particularly for telling her how and when to sing. In an interview with David Ritz, quoted in his excellent biography on Franklin, Luther remembered that “There were quite a few disagreements. Aretha doesn’t like her vocals criticised – and understandably. Hey, she’s Aretha Franklin”.

The Queen of Soul was also unsure of the title track at first, claiming that the the introduction was too long and listeners would switch off before they heard her sing. Luther claimed otherwise, claiming the listener would wait, being hooked on the infectious groove he and Miller had devised. In the same interview with David Ritz, Luther said:

“I wanted to establish the groove with a long instrumental intro. Aretha didn’t think the listener would wait that long to hear her voice. I assured her that the listener would be hooked on the groove and would be delighted to wait. She wanted to come in sooner. I said no. “Who’s the one with the most hits here?” she asked. Of course the answer was her. I just had one; she had dozens. “But who’s the one with the latest hit?” I asked. She didn’t answer. She stormed out.”

Eventually Aretha returned to the studio, and the Jump To It album, as well as a friendship between Luther and Aretha (forged partially on their love of junk food) was born. The title track was a smash: it reached number one on the billboard Hot Soul Singles chart for a month, and helped reinvigorate her career. In an interview quoted by Vandross biographer Craig Seymour, Aretha, no doubt with the benefit of hindsight, claimed that the title song “had all the sugar and spice I required… The groove was extra mellow and the message right on time.”

Indeed, the song helped Arista flog enough copies of the album for it to be certified Gold, giving Aretha her tenth number one R&B album. It was the best performance by an Aretha Franklin album since 1976, when she released Sparkle, a collaboration with Chicago soul genius Curtis Mayfield. Critics, however, were less enthusiastic about the album. Richard Harrington in the Washington Post wrote that “Franklin’s remarkably earthy voice jumps out full force from note one, its pure, accessible, bell-clear tone still a natural wonder after all these years” but that on much of the album “she doesn’t sound challenged” and that her gospel roots had been “washed out in mainstream considerations”.

Revisiting the album thirty-five years later with the benefit of hindsight, and listening to much of the work Aretha released in the proceeding years, Jump To It sounds remarkably good. The title track sounds fresh and exciting, and although the introduction groove is long, Vandross was right: this listener is still hooked. One particular highlight of the album is a duet with the Four Tops: Aretha has always had an uneasy relationship with other singers but the chemistry her and Four Tops lead singer Levi Stubbs was simply breathtaking to hear, and it’s a shame as to why they only ever recorded three songs together, ‘I Wanna Make It Up To You’ on Jump To It, ‘What Have We Got To Lose’ on the Four Tops’ Back Where I Belong album, and ‘If Ever A Love Was‘ on their Indestructible album.

All in all, Jump To It is one of Aretha’s best post-Atlantic records. It was enough to warrant a further Vandross-Miller-Franklin album, Get It Right, but the album wasn’t as strong as Jump To It, despite the infectious title track.

But Vandross and Miller had succeeded in relaunching Aretha Franklin’s career. They had reversed the trend of her declining album sales. It set her up nicely for her 1985 platinum record Who’s Zooming Who, which would yield the huge commercial hits ‘Freeway of Love’, ‘Who’s Zooming Who’, and ‘Sisters Are Doing It For Themselves’ with Eurythmics.

However, for us at TFSR however, Franklin’s work with Vandross and Miller on Jump To It (and later Get It Right) is far superior: the grooves are more infectious, the songs are funky and and it’s less dependent on eighties sounding synthesisers. Jump To It is a wonderful Aretha Franklin album, and it still sounds great thirty five years later.